We are down past the Epipelagic Zone (or Sun Zone) in a submarine named Idabel. Sun light stops penetrating after 656 feet. We go down farther and are down to the Twilight Zone (or Mesopelagic Zone) at around 1,500 feet. The lights go off. It is pitch black. I can only hear the sounds of the submarine and my two sweet kids. I’m holding my breath. Then the lights of the sub flash to life, and turn off again. There was brief darkness and then the bioluminescent phytoplankton flashed their blue lights. The lights came on and off again. The plankton put on their light show. It was like the movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind. This was a show I have wanted to see for years, and this wasn’t even the best part of the dive.

The deep has always fascinated me. My goal is to one day descent to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. My deepwater journey started in 2015, in Kona, Hawaii, with a blackwater dive. The largest migration in the world takes place at night, when the animals from the ocean’s bottom come top to the top to feed. I saw beautiful jellyfish and many other weird creatures. Some had lights at their sides. Other had tentacles coming out. One jelly swam away from us, its purple tentacles going into the abyss–where I desperately wanted to follow.

A few years later, I dove the geothermal chimneys in Strytan, Iceland to see the hot water venting, releasing the nutrients that may have started life. They were the only vents within diving recreational limits. Life thrived around the chimney: sponges, fish, fans. The white vents released their warm water, which we used to warm our hands. I became addicted to the geology of the deep. I wanted to see it for myself, and I wanted to go much deeper.

I searched for a place where I could go into a submersible and see the deep ocean. I found the perfect spot: in Roatan, Hondorus, there was a submarine that went down to 2,000 feet. Whereas other submersibles around the world had to be transported via boat to deep water–a delicate process involving lowering and raising the submersible in careful timing with the waves to ensure the submersible wasn’t damaged–the one in Roatan hung from a dock and could transport itself to deep water.

In Roatan, the island gets deep quickly due to its near-vertical wall, which allows the exploration by sub from the shore instead of from a boat. It is near the world’s second biggest reef: the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System. The reef system forms a near-vertical wall that goes down 2,000 feet. The island was also formed by tectonic tension and magma near the Flowers Bay Fault.

Idabel, Karl Stanley’s submarine, is a marvel to behold. Karl had read a book when he was 9 years old, and his imagination took off. As a teenager, he started building his first submarine and finished it in college. Idabel was the upgraded version of his original. It was made from three spheres. Part of the sub is from a Cessna plane. Another part is from a 57 Chevy. It has redundant systems if things go south with food and air to last three days. It took about 1.5 years to build. He tested it in a deepwater lake, then brought it to Roatan. At this point, it has done more than 1,500 dives. The sub will probably outlive me.

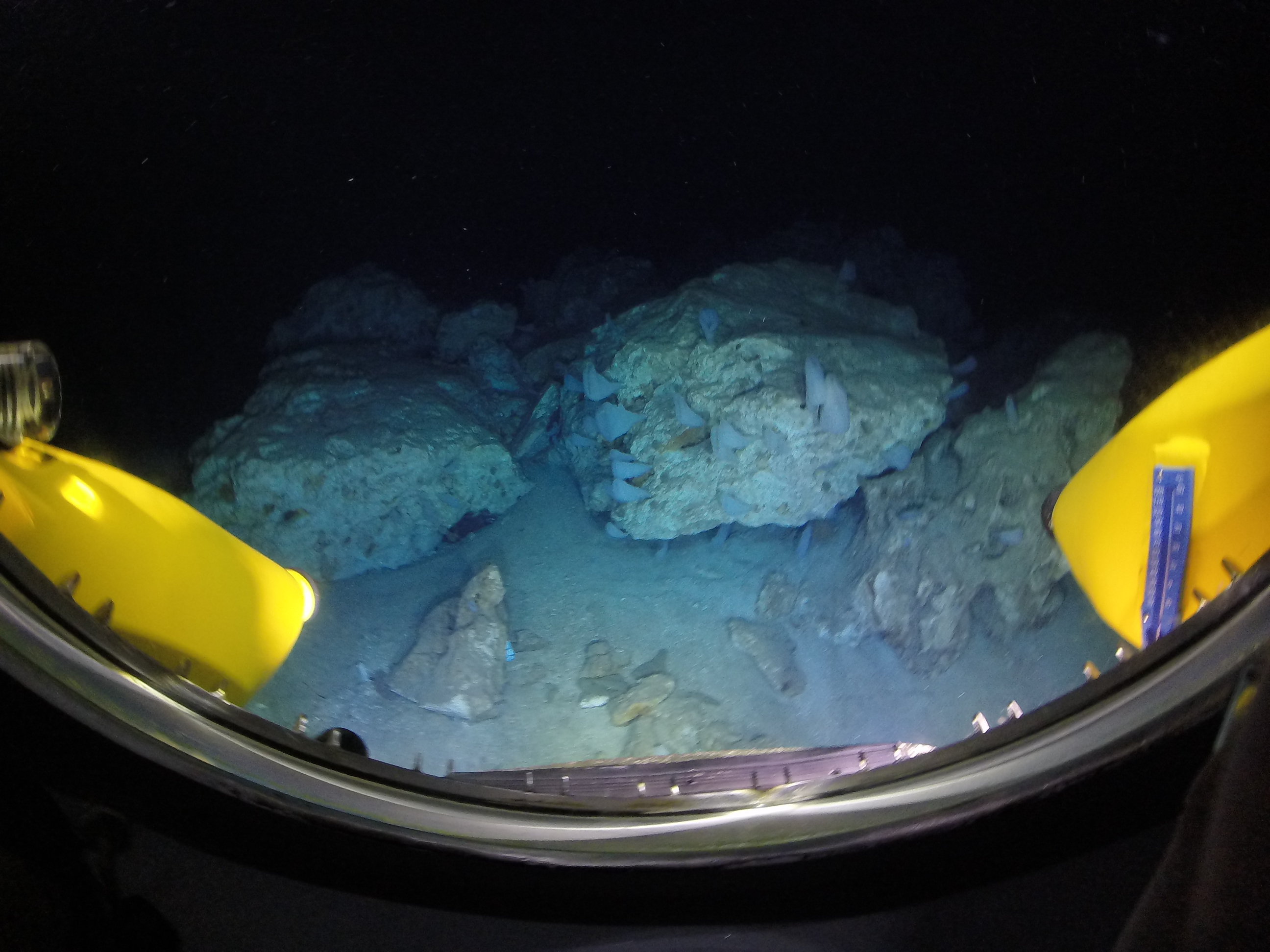

My kids and I got into the yellow submarine on a clear, sunny day. The sub has two windows to look out. We settled into our spots; a crane lowered us into the water; and the submarine started out. The vibrantly colored reef and fish appeared as the sub moved to deeper water.

Very soon, we arrived at the reef wall and couldn’t see the ocean floor. We began our descent. Three hundred feet down, I could still see the sun. Five hundred feet down, I could only see rays of light. The water was iceberg-blue.

Ocean levels have risen more than 450 feet during the earth’s history. To put that in perspective, if all the ice in Greenland, Antarctica, and other places melted right now, the ocean level would rise 230 feet. The change would have been incredible. At this depth, you could see the different rock colorations and how things have changed–like viewing a transcript from Earth’s prehistory. Continuing down into the abyss, all around us was black. Marine snow speckled around the dark of the ocean. This marine snow feeds the reef system farther below. Down at 1,000 feet, the phytoplankton put on a light show. The kids and I played a game of seeing what we could spot. The occasional shrimp would check us out and then run away.

At 2,000 feet, we saw the bottom. The sand looked like the surface of the moon–a place we explore more than our own oceans. A little way out, we saw a red deep-sea toadfish, skulking by himself, for food to swim by. He has a face that only a mother could love. His brother in Cozumel is more of a looker. But to me he was amazing. He alone made the trip worth it.

We searched for boulders that had fallen from above. A lot of creatures like corals and crinoids attach themselves to them. They make their own world on each boulder. The crinoids looked like blue hands. We got to one boulder that had a sea lily: it was stoic on its boulder with a dark background.

At this time, I was craving my Mountain Dew. I had brought one, but Karl had me leave it because of the CO2 in it. Soda really can kill. I had to settle for water. We found another boulder. This one was covered in starfish. Their arms swayed in the current, grasping for marine snow.

Later we approached a yellow sea fan. It had creatures entangled on it. Karl told me some of them live over 1,000 years. Some can live up to 4,000 years. We saw a slowly growing sea fan, growing where not much else could. This fan had been around when Genghis Khan amassed his army, the Magna Carta was signed, the Crusades were fought, the Sistine Chapel was painted, and the United States was born. It was an honor to see such a venerable creature. Best of all, my kids got to see this, too.

My face lit up when I saw a boulder full of crinoids. Previously, I had bought a fossilized crinoid that looked like a rose. Today, I had brought it into the sub hoping to see live ones. Later, I would dip it in Roatan ocean water and give the newly christened crinoid to my wife. On the sub, I could see the crinoids move their arms. I had seen them in so many nature documentaries, and seeing them was like seeing them for the first time.

We saw one fish narrowly escape getting eaten by hiding in a crevice, sparing his life. The fish hunting it had learned the lights attract fish and sometimes uses the sub to hunt. We saw fish hanging upside down to make their silhouette smaller. We saw a spiny crab and another deepwater crab sift through the sand to find a good meal. There was a turquoise blue fish that I couldn’t identify. The blue and red octopus liked to hide from us. Karl had a sharp eye and would find them for us.

We found another boulder and saw a spiky sea urchin. I wondered how venomous it was. I knew some of them deliver a life-altering sting. The creatures of the deep have a great way to defend themselves. The sponges are made from a material similar to fiberglass; touching it would give you painful slivers. My kids and I made funny faces and took pictures with them.

How is taking a 4-year-old and a 7-year-old in a sub with not a lot of space? It was amazing and one of the best ideas I’ve had. They pointed at the cool things we saw. They asked me geology and biology questions. They wanted to know about the animals.

I also got to really talk to my kids one-on-one. We got really close. Their minds have expanded. Tho’ of course, there was also the inevitable “are we there yet?” and, by the end of the 4-hour-trip, “I need to go to the restroom!”

My wife dove with the kids the next day. They saw a group of lionfish at around 500 feet. I was scuba diving while they dove. I saw the sub coming in while I was on the boat. I got close enough to shore, told the captain what I was about to do, and I jumped off of the scuba boat to hear what my family thought of the dive. They were all smiles.

No article about deep sea submarine diving would be complete without mentioning the man, the myth, the legend: Karl Stanley. Karl reminded me of Sir Richard Branson, James Cameron, and Jacques Cousteau. Heroes of mine that changed the adventure world.

I have roasted marshmallows over lava, went diving with great white sharks and manta rays, and explored caves not submerged and submerged in water. After hearing what Karl has done, I had a Wayne’s world moment of saying “I’m not worthy!” I’ve talked with someone that climbed K2, but I never met someone who did the impossible and allows others to see a world that they would never see. Besides all that, he laughed at all my dumb jokes, patiently answered all my and my kids’ questions, and never complained as my kids sang a made-up song on repeat for 3 hours.

This trip also taught me to never give up. I had to work hard to get on this trip. We were going to the submersible in 2017, but our job opportunities required us to move instead. Finally in 2019, I told Karl we could go. Our trip was booked, but then the Honduran government made it really hard to renew its registration. Finally, the day before our flight to Roatan, we got the good news that the registration had gone through and we could go on the sub. Talk about a close one. Later, our flight was late and we made our connection with a minute to spare.

It seemed to me the trip was either cursed or not meant to be. We got to the island and got the exact days booked. Rather than being cursed, I think the trip was a challenge to match how epic it would be. The challenge was that like the creatures of the deep: tough, but breathtaking. My family now wants to live in Roatan.

Danny is an adventure traveler looking to explore areas not known by everyone. He loves to take his curly-headed family on his adventures. His motto is: “a family that dives together thrives together; a family that explores never will be bored.” His family scuba dives, rock climbs, and hikes. Expeditions have included: seeing the Great White sharks, roasting marshmallows over lava, going into the belly of an extinct volcano, diving cenotes and snowboarding the beautiful mountains of Utah.